Warhammer Fantasy Role*Play (weirdly spaced on the cover just so they really nail the “Whifferp” that everyone has been calling it forever) is NOT a game about Time Travel.

Playing it again, specifically gearing up to play The Enemy Within campaign, is the time travel I’m currently doing. This has been ably assisted by the Grognard podcast, delving back through the heady days of 80s roleplaying.

Picture it: Penicuik, 1988, (that’s not it pictured above: too cheery) and a young boy has finally saved up enough money to buy Death on the Reik, a whifferp campaign so big it had to be released in a box. A flimsy, flimsy box, containing surprisingly high quality handout sheets and oddly purple maps, a gazetteer and a thick-ass book containing the substantial plot and characters of this second installment of what was shaping up to be an amazing, long delve into the Gothic Fantasy Horror of the Old World.

It was a Golden Age of Games Workshop creativity, in my opinion, and we had absolutely no idea how short lived it would be. It’s been funny to listen to the Grognard pod’s general complaints about The Great Betrayal by GW and White Dwarf. Because they’re a few years older than me (5 or 6 maybe) their window of what was great and what was a dismal treachery against everything good has been interestingly different from mine. They would have it that I stepped into the hobby during the second Golden Age of White Dwarf but their disgust with the direction of White Dwarf came much earlier than mine.

At this time in the late 80s every White Dwarf that dropped was heralding new GW games, content for old GW games, and great content for other people’s games. It wasn’t slick, it wasn’t even particularly professional, but it was very exciting. After absolutely stellar work for Chaosium’s Call of Cthulhu (which was already excellent) with 1987’s Green and Pleasant Land and the Statue of the Sorceror/The Vanishing Conjurer in ‘86 a lot of the same people were writing for the new WFRP setting.

Was WFRP good? Sort of. The rulebook had layout problems galore, and the rules were so easily cheesed that pretty much every party featured a very tough dwarf that could just do without armour and shrug off axe blows through sheer gritted teeth. To their credit, GW absolutely ran with the Naked Dwarf Tank build… The setting was great though, playing off Cold War-era paranoias of nuclear horror, society’s corruption and subversive politics, and presenting their Old World setting outside of the context of grand battles between massive armies. 40k sold itself (very, very shortly after) as a setting where there was Only War. But they’ve also benefitted from looking at life far behind the front lines, as a great deal of their best fiction deals with corruption on the home front, and if the blessed Saint Henry Cavill wills it we may see this developed even further.

Paranoia and Call of Cthulhu, both of which GW held the UK license for and supported, also deal with the same thing: society being undermined by people, aided by comical misunderstandings/Beings Beyond Mortal Ken Etc. But applying it to a Fantasy setting, even a grubby fantasy setting like the Old World made for a really fun game where you could axe orcs to death, smash skeletons to bits and then also finger greedy burgomeisters as witches because you broke the code on their secret society robes and used it to research accounting ledgers that showed that they were behind the brain fungus drug that pacified the Stevedore’s Union.

It was obvious from the start that WFRP combined the investigative chops of CoC with the fantasy tropes already troped to bits by D&D and other fantasy games. This is clear especially in how Death on The Reik was presented: with maps of places that you could bust into and loot/murder through, sure, but also with the atmospherically appropriate found letters, player handouts and bits of Old World lore that players would brush against.

All that would take us a while to get to back in 1988, I spent many a summer’s day with the tent set up in the back yard, creating character after character. I still smell warm camping tarp when I look at some of the careers pages.

I ran a few daft wee things, basically before we really knew what we were doing and I’ve come back to the game a few times to run odds and sods. But for as much as I love it, it was never the most played game: we moved into Middle Earth Roleplaying, Shadowrun, James Bond as well as various other things on shorter bursts.

I decided to run Shadows over Bogenhafen and Death on the Reik maybe 15 years after I got it for Mike, JIM and Dieter, having hauled that increasingly fragile box across the Atlantic. After that I think we played a bit of WFRP beyond the campaign.

I picked up the second edition (seemed very good, never played it) and avoided the third edition. It was the deluxe Director’s Cut version of the Enemy Within campaign that made me pick up the 4th edition.

Rules-wise and in terms of organization, the 2nd and 4th were far superior. and they seem well supported in a way that the original famously wasn’t after The Enemy Within. We were promised a magic book, Sigmar-damnit!

So while I’ve never really played it for a long time, beyond the Enemy Within, why do I still think of WFRP as this personal touchstone RPG?

It’s a puzzle, but I think in general it is the setting. The rules have some neat bits, especially the 4th edition, with its degrees of success mechanic and its magic number 9 (which honestly reminds me of Terry Pratchett’s magic number that must never be mentioned between 7 and 9 and rhymes with late). But I think it has to be the setting and that – as a fantasy setting – has a LOT to commend it.

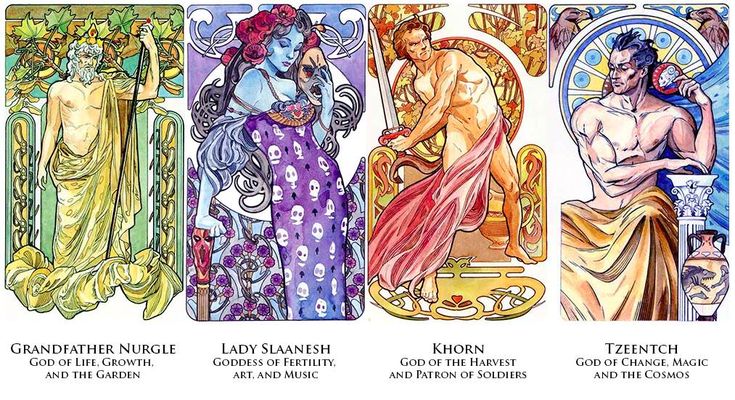

As villains, The Ruinous Powers are excellent. Both because as untouchable cosmic horrors, they work really really well and in their lesser physical manifestations they work really well. I think that’s because they are prey on absolutely normal human feelings/failing, as opposed to the more abstract unknowable Cthulhu Mythos beings. It makes them seem more inevitable. The four chaos powers, Khorne/Nurgle/Tzeentch/Slaanesh, War/Plague/Sorcery/Excess or Wrath/Despair/Ambition/Desire, or Hound/Crow/Serpent/Eagle… however you want to put it… are really good adversaries.

There are other antagonists, of course, mostly falling within standard fantasy tropes. Within the well-established setting the Vampire Counts, urban-legend Skaven and Wood Elves (very much not-default-friendly-elves) make decent adversaries with rich backstories upon which to draw. The other big Warhammer Fantasy Battle factions, your Lizardme- Seraphon sorry, greenskins and Bretonnians are all a bit too broadly-stroked to see how they would fit into a game. I mean, if one Orc shows up, a whole Waaaagh of them tends to show up. The best antagonists in WFRP, in my opinion, are regular people. Or at least that’s how they started off…

The other thing that the setting has going for it is Class. That’s a product of pinning it to a Renaissance era Northern European-ish. You’ve got society moving from a Noble/Serf feudal society to a Noble/Burgher/Worker capitalist society at differing rates of speed and creating some great friction. That’s another amazing side-effect of being written in the 80s, especially in Britain and especially by the crew of writers who put it together. The social structure of The Empire and the way it plays out in the game deserves it’s own post, so I’ll write about that some other time.

A lot of good games have some other conflict as a backdrop to the conflicts that the players may be getting into. That isn’t new. But conflict, open and clandestine is all around in WFRP in a way that it isn’t really in MERP’s time period or the very static-seeming setting of D&D. Star Wars has a big conflict going on but what kind of player doesn’t want to help the Rebel Alliance? Jeez.

So in summary, tl;dr etc: The rules are fine, although I can’t imagine ever being enough of a fan of the ruleset to think “I wish I could port these rules over to another setting”. It is the setting, strengthened by parts of the rules system and especially the setting as expanded upon by the supplementary material for the game that make the game so dear to me.

The mixture of cosmic horror, adventure, social commentary and high stakes violence that so appealed to me in the summer holidays of the late 80s continues to be a high I’ve been chasing ever since.